A Few Doubts About A Few Doubts About Romanticism

A Note on Matt Gasda’s criticisms of the New Romanticism vogue, Neo-Romanticism, and The Need for a Romantic Revival.

Matthew Gasda has recently offered some useful criticisms of the new romanticism trend, as promoted by writers such as Ross Barkan and others, here:

I too have been promoting a neo-romantic project for the last several years. My book, Against The Vortex: Zardoz and Degrowth Utopias in the 1970s and Today, which excavates a radical neo-romantic segment of the counterculture that I call “Critical Aquarian” is arguably a new romantic manifesto.

But the romanticism I seek to revive differs in many ways from both the current discourse and the purely expressivist or subjectivist romanticism Gasda describes. I believe, following the work of romanticist scholars and thinkers, that early romanticism offers us a radical social and ecological vision, among whose heirs are Morris, Kropotkin, and the later Marx (see Kohei Saito on this last point), rather than Poe or Baudelaire. The early romantic project presents a model for building another world among the ruins of our industrial capitalist nightmare.

I am of course starting from a different place. For me, revolution, definitionally destructive, is often necessary: in the 1790s and perhaps again today. I am also, in keeping with these commitments, a lifelong partisan of the prophetic mode.

Gasda nonetheless makes many salient points as when he writes: “The best of Romanticism is highly private. It’s not on the internet. It’s not discourse. It’s not a vibe. It’s in the mind, in the body; it’s a frequency of the soul — at its best and purest. The Romantics were willing to die for love. Yes, they were willing to die for revolution, but they were also willing to die for poetry.”

He is right that, for example, what is being called neo-romanticism is, like nearly everything else at this point, mediated by the internet, and this holographic mediation of life and thinking represents a betrayal of the embodied immediacy championed by various romantic thinkers and poets. But then again we are also seeing the return of Luddism, from August Lamm’s rejection of the smartphone (a minor Zoomer movement) to Luigi Mangione and the Kacszynski revival, which I wrote about on Substack.

The cultivation of intense feeling was a significant component of historical romanticism, but the romantics did not understand this feeling as either wholly private or individualist in nature, especially if we recall the centrality of Stimmung or mood to romantic thought and practice (more on which below). This is where the work of scholars and thinkers, from Frederick Beiser to Michael Löwy, are useful. See, in particular, Beiser’s Enlightenment, Revolution, and Romanticism.

The romantics didn’t reject enlightenment or rationalism so much they called for a more expansive version of reason, encompassing imagination, feeling, embodiment, and our continuities with the natural world. Theirs was an immanent critique.

The self was vehicular for the romantics, from Wordsworth and Coleridge to Schelling, Hölderlin, and Schlegel: the gateway to divinized Nature and non-alienated modes of an imagined quasi-socialist communal life.

Recall Southey’s and Coleridge’s Pantisocracy in this regard. Or how all of these figures were avid partisans of the French Revolution, at least early in their lives (before a few of them became conservative later on, often abandoning their romanticism). Hölderlin was an unrepentant Jacobin into the early 1800s. And both first and second generation English romantics were all partly in thrall to Godwinism (the Shelley’s obviously) at least in its political dimensions.

All of these early romantics wrestled with the problem of reconciling individuality with collective life. Many of them—Blake or the early Coleridge and Schlegel, for instance—also saw how possessive individualism, the mechanized division of labor, and the triumph of exchange value led to an enforced conformity. The early Marx took up this insight in his first theorizations of alienation; Marx understood communism as precondition for a more capacious individuality—hunting, fishing, criticizing without becoming hunter, fisher, critic.

Gasda correctly stresses the primacy of romantic love for the romantics. But was their model of love a strictly private affair? And I am not referring to Shelley’s (or Byron’s) well-known advocacy of “free love” in this case. Blake consistently envisions the ways in which erotic love is both prerequisite for and expression of agape, the love of God and cosmos:

Love and harmony combine,

And round our souls entwine

While thy branches mix with mine,

And our roots together join.

Joys upon our branches sit,

Chirping loud and singing sweet;

Like gentle streams beneath our feet

Innocence and virtue meet.

Thou the golden fruit dost bear,

I am clad in flowers fair;

Thy sweet boughs perfume the air,

And the turtle buildeth there.

There she sits and feeds her young,

Sweet I hear her mournful song;

And thy lovely leaves among,

There is love, I hear his tongue.

There his charming nest doth lay,

There he sleeps the night away;

There he sports along the day,

And doth among our branches play.

And isn’t socialism or communalism at its best the political manifestation of love?

Romanticism was certainly in the body and the mind and the soul, as Gasda contends, like a spring wind making music as it blows through an Aeolian harp, which is why I disagree with him regarding the “Vibe” and vibes. Romanticism was very much a vibe in the sense of “Stimmung” or mood. Stimmung is a central category in German romantic thought that traverses thinking and feeling, subject and object, inner and outer: the weather out there and the weather in our heads, bodies, by ourselves and altogether.

It was Martin Heidegger who later developed Stimmung into one cornerstone of his philosophy in Being and Time. Heidegger writes “the mood has already disclosed, in every case, Being-in-the-world as a whole, and makes it possible first of all to direct oneself towards something.” Stimmung is a kind of attunement: how we vibe with the Vibe or Da-sein.

I would here note that this idea, rather than the term, isn’t unique to the German romantics or their Central European philosophical heirs. Consider Shelley’s model of the human mind as an Aeolian harp in his A Defence of Poetry—which he further refines in terms of a conscious harmonization between the inner and outer worlds by way of the poetic principle. Shelley offers us a powerful definition of mood. He also, I think, perfectly captures “vibes”(using the analogy of literal vibrations as he does):

“Man is an instrument over which a series of external and internal impressions are driven, like the alternations of an ever-changing wind over an Aeolian lyre, which move it by their motion to ever-changing melody. But there is a principle within the human being, and perhaps within all sentient beings, which acts otherwise than in the lyre, and produces not melody alone, but harmony, by an internal adjustment of the sounds or motions thus excited to the impressions which excite them.”

I am focusing on Stimmung as Vibe here because this (non-conceptual) concept exemplifies the romantic refusal of the often pernicious dualisms that have defined Western modernity since Descartes and the early modern European scientific revolution of the seventeenth century. These binaries include mind and body, of course, in addition to culture and nature; they also cover reason and passion, private and public, individual and collective, poetry and revolution.

For the romantics, in general, and Shelley, in particular, keeping his “unacknowledged legislators” in mind, we must refuse both the oppositions and compartmentalizations of the dominant modern worldview and approach these different modes of life and activity relationally. Long before ecology, romanticism was a supremely ecological project. Why we need it more than ever in our necrotically monocultural twenty-first century.

Part of the problem is terminological and historical: using “romanticism” in a way that includes later, arguably decadent, neo-romanticisms—Poe, Baudelaire, Rimbaud, symbolism, etc. Different sensibilities, often “against Nature.” Whereas that early generation offered us an ecological vision aimed at the Industrial Revolution (and empire)—from Blake or naturphilosophie to Frankenstein—at the very inception of Fossil Capitalism. Here was a first, pantheistic, iteration of eco-socialism. Anahid Nersessian meticulously details the romantics’ attempts to think utopia and natural limits, infinity and finitude, together in her Utopia, Limited (highly recommended). Utopia and limits, emancipation and tragedy must be at the center of any radical political, social, cultural, and artistic movement in our current moment of existential peril.

So while I agree that the current talk of neo-romanticism is empty (where is the neo-romantic literature now? What distinguishes it as romantic on a formal level?), I also believe that romanticism in its first flush and certain later iterations (Morris and pre-Raphaelitism, certain versions of transcendentalism or our belated US romanticism, surrealism and situationism, what I call Critical Aquarianism in my book) offer an alternative vision of social life for us in the present age, beyond the figure of the congenitally irrational and emotionally disturbed poéte maudit. Examine the recent work of Charles Taylor and Eugene McCarraher, among others, in this regard.

Finally, while I don’t think that we have anything like a new romanticism now, whatever the various purveyors of the discourse say, we certainly need such a romanticism in its most expansive sense.

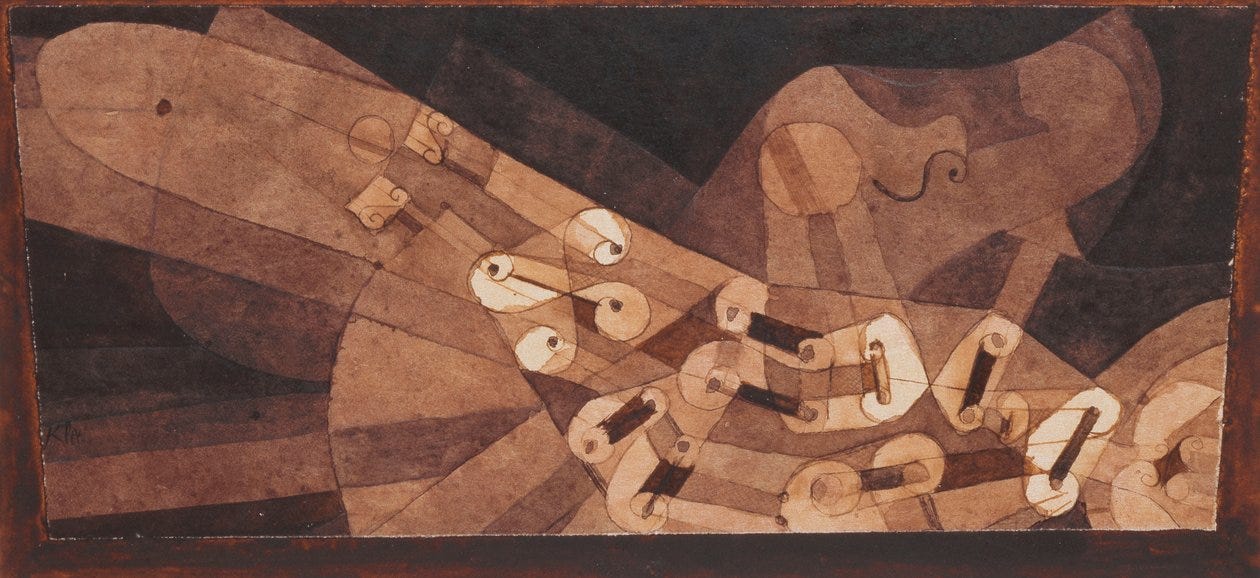

*Rather than reading the often solitary figures in Caspar David Friedrich’s work—rear view proxies for us, the viewers—as exaltations of solitary genius, we might instead see in them that other, pre-Kantian, version of the sublime: the smallness of the individual in the face of Nature, Time, and the intergenerational human and non-human creaturely community that is so much bigger than any one of us…

We must change our life.

This was great of course. But I’m having trouble squaring the idea that Romanticism is a variety of socialism, or even that it’s sympathetic to socialism. The most obvious point for me is that they tended to oppose progress — Frankenstein is a clear example, but Byron in Childe Harold states outright that history is in a process of decay. (He also says that this might only be solvable if a heroic warrior of the old Greek type were to surface and lead Greece, for example, to regain its former glory.) Shelley also in Queen Mab says that civilization is a corrupting influence and that we’re meant to return to the state of nature. A return to the status quo ante isn’t exactly a type of progress.

Maybe this is just a feature of the English Romantics, but it seems to me that their primary outlook is somewhere between the aesthetic and the religious, and that their desire to reverse progress and return to a former way of life has to do with reclaiming a vitality that they saw as lost. Obviously they were interested in politics, but when they addressed it they tended, like Blake, to frame it in terms of religious, cosmic and aesthetic categories.

Anyway that’s my reading but I’m happy to admit I’m wrong.

It’s interesting about the romantic love aspect of things, because in a way it never really is private. Even when people attempt to make it private, it spills out into the collective through our many threads of connection, into our stew-pot families. Thinking of these connections as “all our relations” as Indigenous Americans might say, the effects of private intimacies become public, in the way a particular coupling can be a good thing for community or through drama, cause more problems for everyone. Thus the private is political.

About the vibes: cultivating a sense of aesthetics, or as the arch-Goth and symbolist (and sorcerer) Joseph Peladan might have it, an ethopoesis. This creation of character is critical in a time when reality is mediated by spectacle and absorbed in simulacra. The way we might create character can be embodied in our activities offline (going to art/music shows, readings, long hikes, walking our pet lobsters). Yet we have the internet for now, and one way to spread the stimmung is through this discourse, and revitalize some of these interrelated movements by getting people interested in them.

P.S.: I’m looking forward to your book, I’ve ordered a personal copy and will put in a request for the library I work at to pick it up. The 1970s were also the age of appropriate technology, a movement those of us interested in degrowth, and things like selective Luddism could glean so much from.