S. died in later April, over two decades ago, at the age of 23, a few months shy of her June birthday. I hadn’t seen or spoken to her in nearly a year. I spent another night away, from my then Upper East Side residence, with a friend—to avoid my father. I was sharing the place with him, a man I despise, after he’d temporarily moved my mother and brother to Florida, with its lax bankruptcy laws, for a year or two to avoid his various vexed creditors.

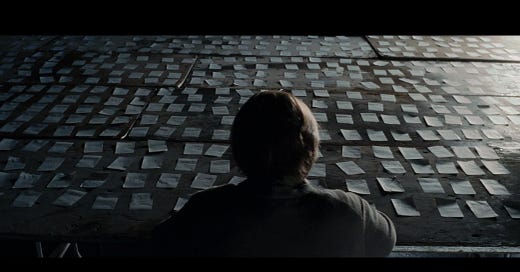

I can remember trudging back to my building, across the park in the early morning April sun, to discover my “dad’s” anxious and incoherent note alongside a storm of answering machine messages from high school friends: people I hadn’t heard from in a few years, which felt like forever back then.

“I am sorry. S. is dead. We don’t know how or why,” they all said in various tones of confusion, resignation, and dread.

I got one of them on the phone: “ I don’t know, man. I heard this from my friend who knows her sister. She was at NYU.”

I was in a state of stun when I learned, from a mutual acquaintance, that she wasn’t dead but in the ICU at Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital. I remember hailing the cab uptown, consoling myself as I insulted the presumptuous idiocy of various gossip mongers in my head.

When I arrived at the hospital, her siblings saw and called to me, weeping. S’s then-current partner was also there. It had been nearly a year. We hastily shook hands, but I didn’t care under the circumstances. Then I saw her parents: a big, old brute of a dad and her much younger mother who explained the situation to me.

S., who was living in Hell’s Kitchen, caught a cold that swiftly increased in severity: chest pain and breathing difficulty. Her boyfriend took her to NYU Langone, where they determined it was viral myocarditis: a virus that attacks the heart and sometimes kills you. Her case worsened and the ER team decided she should be at Columbia-Presbyterian, with its supposedly superior cardiovascular disease treatment tools and facilities. She died on the way uptown in an ambulance stuck in midday midtown traffic the afternoon before, but the EMT crew managed to revive her. She was gone too long however. I arrived at the hospital immediately after the family decided to kill the respirator.

“You two were together on and off for such an age, Anthony. I know we always didn’t get along, but you should say your goodbyes. We all are,” her mother whispered in a halting way.

I met S. in high school. She was a child actress who ditched a “professional children’s school” in her last year to attend a night program that rented part of my private Manhattan HS in the evenings. She was sitting in on my International Baccalaureate theory of knowledge class for whatever reason: how we met.

She lived in a cramped apartment alongside her brothers, sister, mother, and a mercurial father with a short fuse; like many professional child performers, the family often lived on her residuals. If you have a kid, don’t sell her to Hollywood, or so I learned. We’d often sneak into the stairwells.

I went to college, in New York, and she moved to Los Angeles to pursue her acting career. Yet she appeared and reappeared in my life intermittently over three years of university. I got her pregnant. At 20, I made entirely ornamental noises about keeping the baby; yet, after she died, this thing weighed on me in particular. In my final year of college, she’d returned to New York for good, wanting to get out of the great American skin trade and pursue a degree or write—she was a good writer—and we started dating again.

She found an apartment for us. We lived there for several months. She was happy. Then I cheated on her, with another actress: a future Law-and-Order spin-off worthy. As my parents guaranteed the lease, I finally asked S. to leave, thinking she’d always be there at some unspecified future point, giving me enough time to collect the kinds of experiences, sexual and amatory, a young man is supposed to amass. As Scott Walker sings in a late masterpiece of a ballad:

I knew it was love

But when you are young

You think love will come again and again.

Miss Law-and-Order ran off shortly thereafter of course, but the burden of guilt was no match for my puerile narcissism over those months. I didn’t talk to S. during that stretch of time. I did later learn that S. was leaving messages with my father shortly before her sudden death, but he is absent-minded so…

I crept into the antiseptic hospital space, a makeshift room made from those plastic curtains characteristic of intensive care units, fusing shantytown and high tech in that distinctively disconcerting medical-industrial way. She was slightly blue and long gone. I assumed, when I last saw her, that I would see her again when I was ready to settle down, awash in the blithe arrogance of young male fantasy. And this was how I saw her last—each of us had about a minute alone with her soulless body—but I didn’t know what to do or say. I stood there, trembling, the last of S’s visitors, before her entire family and new partner crept into the unit. Then we stood there, crying, as technician and doctor ended what was left of her.

I spiraled into the year that followed: from semi-suicidal drinking binge to monastery respite to stint in the Arctic circle, telling myself all the while that I’d learned the lessons. Humble and all the rest: take no one for granted, Anthony! You might think that such an early loss would teach us to cherish everyone in our orbits, but it instead led me to avoid attachment and hide whatever emotion I did develop: because you never know.

While that year arguably laid a foundation—and I am arguing with myself about it still—how many decades did it take to become a somewhat better person? I like to tell myself I should have died instead, but that is vanity; if anything, I sometimes wonder if, in certain ways at least, I stopped developing at 24, and how many women had to deal with the stunted outcome? I’ve learned to be open in my attachments over the last several years, even as I often overwhelm—ironically shifting from “avoidant” to “anxious” register—perhaps from too many years of feelings denied or repressed. This kind of thing doesn’t work so well in our age of high tech erotic individualism, which is something I, of all people, should understand. More ironies.

In an incisive post regarding the most recent season of White Lotus, the writer pivots from his reflections on Sam Rockwell’s Frank and Walton Goggins’s Rick, two shipwrecks, to a blunt meditation on the human sacrifice it often takes for men to change: “To be part of a group that so often needs to be taught kindness, fidelity, presence, through pain and punishment. It is shameful. There is not really another word for it. Shameful that we do not listen until it’s too late.”

Since that long ago brutal spring, April and its season have established themselves in this fort/da game of a life as my bloodletting time of year: a season of breakups, breakdowns, and failures of all kind.

“April is the cruellest month,” or so T. S. Eliot famously begins The Waste Land. Despite the born-again Eliot’s later dismissal of his own great poem as a lot of “rhythmic grumbling” or “a personal and wholly insignificant grouse against life,” he is riffing—in “The Burial of the Dead” and throughout the work—on the idea of spring as the season of rebirth. He invokes, as any undergraduate once knew, The Canterbury Tales and various fertility myths in the thing itself, then in his Notes; but, whereas the blood and sacrifice that accompany rebirth rituals traditionally lead to regeneration, the post-WWI modern order was, for Eliot, all pain and chaos without rhyme or reason (hence the poem’s fragmentary form).

On a more personal scale, spring is a liminal state, split between cold and warm, caught between winter and the golden days to come. Transitional phases and initiation rituals are painful, especially in the absence of any obvious end point to the rite. Eliot—a scion of Boston Brahminism raised in St. Louis, an American who reinvented himself as British—was perpetually out of place in a way that resonated with the displacements of a catastrophic modern age. Then he found religion, and a resurrection narrative that bested even the best myths of vernal rejuvenation. Lucky those who can believe and luckier still those whose lives accord with such beliefs.

Meanwhile for some of us—such a thing, too many things—it is too late.

It's too late and never too late. It's even sadder and more beautiful. More love and heartbreak, and more cruelty. World without end.

“I knew it was love

But when you are young

You think love will come again and again.”

I don’t know if regret is the right sentiment, or lost or loss, perhaps? Maybe there is something that embraces all three — things that were and yet might have been; never realized to their full blossoming except in our hearts after they’ve gone. Dickens wrote, “There was a long hard time when I kept far from me the remembrance of what I had thrown away when I was quite ignorant of its worth.”