“Never double-text. Girls don’t like that now,” my friend explained to me.

“Why?” I asked.

“It means you’re needy.”

“What?”

No reply.

Double-texting broadly refers to sending several text messages to someone before they respond to any one of them. Even one or two text messages that aren’t directly solicited might be perceived to violate the ever multiplying “boundaries” which mark off the stunted—permeable yet brittle—self in the age of the internet.

The irony here is that text communication as such is a non-intrusive and relatively impersonal form of abbreviated exchange already—a digital version of telegraphy and telegraphic communique—especially when compared to the telephone calls texting has replaced. The phone call is now a dreaded thing for most people under the age of 65. One Gen Z interlocutor told me she feared the phone call because “you have to constantly fill up the silences. You don’t know where it will go. You can’t control it.”

You could always hang up, but that is an aggressive act, and one which reminds us that the phone call is still one step removed from face-to-face contact and its uncertainties. Although what the phone call still retains is the voice of the other; the human voice, besides expressing feeling of all kinds, can persuade and seduce us into situations and commitments good and bad.

Text messaging represents yet another remove and requires even less: a few seconds to tap a one- or two- or three-word response, yet so many of us now experience this convenience as a burden. We might see in this feeling a kind of inchoate protest against the 24/7 availability enabled by the digital technosphere, even as so many simultaneously prefer texting and screens to human contact exactly because we want to control it.

The urge to control “it” is also the urge to control “ick”: contact between human beings with all their icky mess and surprise. This existential germophobia reveals why the text message has supplanted the phone call, the human voice, and, by extension, presence itself. You can text back if you want and when you want—today, next week, or never. Although, in the last case, if you’re the one on the other side of the digital ghost strike, this shadow simulation of human relations often feels like Vladimir and Estragon waiting for Godot: “tell him you saw us.”

Is this the silent treatment as social more, or is it social sadism? Will you pass the test? Many won’t since this kind of calculated withdrawal might also incite an angst-riddled volley of shrieks into the void or at least a repetitive drumbeat of texts: hello? hello? I am here. I am here. The human desire for recognition is fundamental, as G.F.W. Hegel understood at the dawn of the modern age, but now, according to the terms and conditions of our catabolic capitalist digital shit circus, to act on this desire can be an epic fail. I guess there really is no sexual relation. Or any relation whatsoever. Is it any wonder that attachment theory is having a boom when our digital dispensation is better described as an assembly line for the mass manufacture of anxious and avoidant attachment styles?

But shouldn’t I at least celebrate all this writing as a downwardly mobile and perpetually disgruntled English teacher? Rather than ushering in some second great age of epistolary lit, text and social media communication have transformed written expression into “text speak” or post-literate code: minimalist strings of acronyms, words reduced to homophonic letters (Wut u doing?) and emojis. Here we can see Marshall McLuhan’s media determinism in action as the kind of long, densely figurative, and rhetorically adroit language that defines writing as a reflective and expressive medium—i.e. literature— and by which the written word replicates, or even extends, the persuasive and seductive powers of the human voice is precluded by our thumb tapping twittering machines. (And to attempt texting in a literary way is to invite unread texts and unseen ridicule.) Finally, it is exactly the telegraphic qualities of text speak that make text messaging a notoriously bad medium for conveying subtext and tone. As most of us have experienced first-hand, texting is more accurately described as a medium of miscommunication.

Dating—that most intensive pursuit of human connection—has been thoroughly transformed by these new technological forms as they have transformed the humans who seek to connect with each other. Courtship has always involved rituals, etiquettes, and games but now it seems that’s all there is.

Although I was nearly a year single after a long-term relationship came to a terrible end—then light found me again outside the blinking panopticon at least for a bit—I still find what passes for dating ritual and etiquette in our desiccated present inexplicable at best and abominable at worst. I do know that too many are miserable and lonely. Yet these same complaining people all participate in a game now almost wholly mediated by screens, social media platforms, and dating apps—a game that includes tacit prohibitions against “double texting, ” among other pathological norms—in which any demonstration of interest or feeling, particularly early on, is a “red flag” (this game is notably permeated by the noxious jargon of pop therapy) since this points to need and needs.

We are, in the notable formulation of philosopher Alasdair McIntyre, “dependent rational animals” while the quest for companionship and love is, almost by definition, a quest for a more interdependent form of being together (nowadays pathologized as “codependency”). Against this, our common creaturely condition, we’re instead all enjoined to emulate the callow frat boy or the slightly sociopathic player who never calls you back.

At least we can say we’ve achieved something like gender parity in this area as women join men in the widespread rejection of sentiment and “neediness,” today embossed with invocations of self-care and going our own way (brothers and sisters going their own ways doesn’t portend well for the society, does it?). As you have probably guessed, the focus of this essay is heterosexual pairing of a monogamic stripe and its sorry state, as we can note in the all the recent talk of “heteropessimism.”

Much has been written on the many ways that Tinder, Hinge, and the rest remake intimate life into a pernicious version of online shopping as they transform potential mates into so many collections of data points to be combined in the most algorithmically efficient fashion. Of course efficiency in this case consists in retaining the users who would dispense with the app if they were to succeed in finding significant others: why failure to mate is built into the architecture of these systems. But I believe these systems would fail in any case, even if designed with the best of intentions, since attraction, not to speak of love, has an irreducibly qualitative dimension.

Jean-Pierre Dupuy invokes the Ancient Greek myth of Amphitryon in this regard. Zeus desires Amphitryon’s wife Alcmene; Zeus accordingly transforms himself into a perfect simulation of Amphitryon, yet Alcmene recognizes the Olympian imposter and rejects him. Dupuy concludes: “When one loves somebody, one does not love a list of characteristics, even were it to be sufficiently exhaustive to distinguish the person in question from everyone else. The most perfect simulation still fails to capture something, and it is this ‘something’ which is the essence of love, that poor word that says everything and explains nothing. I greatly fear that the spontaneous ontology of those who wish to be the makers or re-creators of the world knows nothing of the beings that inhabit it but lists of characteristics” (258-259). Dupuy—writing in 2007 on the ethics of nanotechnology and the transhumanist project—accurately predicts the data point ontology that undergirds the dating app and its anhedonic economies of matchmaking.

A little bit of technological determinism is in order here. While I am older and recall a time before the simulacrum of life in the digital hologram, this is certainly not the case with many of the people participating in the game. More used to interacting with social media avatars—trolling and blocking—we can now observe this virtual poison as it spreads through the flesh-and-blood, if algorithmically managed, social body. Which is why psycho-pathological tics out of the DSM-IV--like ghosting, splitting, and the kind of troll show performance that precludes any trace of vulnerability—are our new norms and imperatives.

This process arguably represents the last stage of the rationalization process described in different ways by Karl Marx, Ferdinand Tönnies, and Max Weber or their followers. In the past, you met your dates, partners, and future life mates through those longstanding networks of extended family and friends that roughly correspond to the idea of Gemeinschaft (“community”) as theorized in the German sociological tradition. It was exactly the primacy of communal ties, with their attendant obligations and consequences, that precluded behaviors like ghosting. You had to deal with your friend’s sister or your brother-in-law’s nephew if you wanted to split, or else. You couldn’t just vanish.

With the shift into Gesselschaft (“society”), impersonal contractual relations—along the lines of wage labor, business transactions, and market calculations —increasingly colored all interpersonal connections, including intimate ones outside of the public sphere. In this story, internet dating and its swipe right “culture” of exchangeable shopping options are one reified end point of the capitalist modernization process and its colonization of the lifeworld.

While these ideal types are useful in deciphering long term historical and social transformations, this narrative is too simple. The marriage contract, for example, was for most of recorded history just that: an arrangement among families until the ideal of companionate marriage was adopted as a western norm during the modern period. And, as Marxist feminists like Silvia Federici argue, after the decline of the household economy, rather than a haven in a heartless world, the intimate sphere of women, children, hearth, and home is a reservoir of reproductive labor: the unpaid foundation for the paid work upon which capitalism depends. This is reductive of course—the bourgeois family can be many things at once, both good and bad—but a useful reminder nonetheless.

Until the day before yesterday, romantic love had always existed in the interstices and among the shadows—passion arrayed against formal reproductive arrangements—as we can see in the medieval literature of courtly love with its focus on unrequited, idealized, and tacitly adulterous longing. The union of love in this sense and formal partnership arrangements that include children is a modern achievement—mostly a good one—in part attributable to romanticism, modernity’s first counterculture. The virtualization and quantification of erotic life by way of digital prostheses represent a bad break with this more recent hybrid tradition.

Yet so much of our new ethos recalls the rake and the flirt in automated and algorithmic forms. And, as our perennialist critic might object, you only have to read Samuel Richardson or Jane Austen to know that libertinism and coquetry—very much aligned with letter writing and the epistolary novel at their high points—long predate the internet. Perhaps, but what was once exceptional—hence the stuff of novels—is now pervasive in a mechanically unconscious manner, as the dominant etiquette increasingly resembles a cluster b personality disorder.

The libertine ethos was always a quantitative one anyway, from Lord Rochester to the Marquis de Sade: the higher the body count the better, with bodies-conquests understood in blatantly material-mechanical terms and often accompanied by explicit commitments to the most reductive forms of materialism and/or rationalism. (Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer first recognized this kinship between a certain strand of enlightenment rationalism and Sade’s libertinism in their Dialectic of Enlightenment.)

Coquetry similarly revels in successfully conquering and cultivating suitors, admirers, fans. String them along. Crush them. Record the wins in the journal-spreadsheet. Post the wins on your IG story or incorporate them into your OF routine. The game—which encompasses both internet instilled interpersonal mores and the algorithmic dating machines whereby the Sadean utopia of bodies as numbers and nothing but numbers are realized—represents an old dream of reason come to “life.” We have arrived at something like a high-tech proof of concept!

Meanwhile—and with techno-material base and memetic superstructure in mind—is it any wonder that we today see an explosion of praise for transactional relationships on both the libertarian right and an ostensibly Marxist left? Ours is a zeitgeist both incoherent and ironic. Consider our frothing US right wingers who see “cultural Marxism” in the moralizing technocratic liberalism of the DP, while too many self-described, extremely online, American Marxists believe that the abolition of capitalist property relations are simply one utilitarian precondition for the realization of various self-interested enterprises. These enterprises are indistinguishable from libertarian visions of freedom (even as they are inconceivable outside the capitalist cash nexus—I-Phones for everyone?) So much for the pursuit of a non-alienated life! And right, left, center are all of course equally techno-utopian.

As the most incisive technology critics—from Ivan Illich to Langdon Winner—have noted, social and technological determination are inextricable from each other. A big chunk of the same generational cohort that grew up in these various virtual worlds were simultaneously raised as so much human capital by helicopter parents who instilled in their offspring a neurotic fear of life and its messy contingencies; these tendencies were (and are) magnified by digital platforms that instill in their users the illusion of control (even as Facebook, Instagram, and the rest mine and manipulate them, mine and manipulate us).

We can, in other words, detect in the game playing that characterizes so much of our hypermediated dating—so much of our hypermediated interpersonal—lives a fear of life (and feeling). Hence “red flags” and the tacit hoops: tests animated by a delusional urge to immunize us against present and future failure, heartbreak, and loss.

But these things—and the possibility of failure—are exactly the point as Martin Hägglund contends: “Caring about someone or something requires that we believe in its value, but it also requires that we believe that what is valued can cease to be. In order to care, we believe in the future not only as a chance but also as a risk. Only in the light of risk—only in the light of possible failure or loss—can we be committed to sustaining the life of what we value” (10). It is within the horizon of finitude that any commitment has weight as you or I embrace the risk of committing to this person or that project, knowing such risky commitments could very well come to nothing or worse. Feeling powers such leaps of faith.

And what is this feeling? Love. The discourse on love is a long and complicated one. If we don’t have love, it’s all for nothing, right? St. Paul is correct but he’s talking about another kind of love—charity, agape. I have come to believe that the different sorts of love —philia, eros, agape—are permeable, that these are overlapping magisteria.

When Socrates ventriloquizes the priestess Diotima in Plato’s Symposium, Diotima offers us love as ladder: we move from erotic attachment to a particular person to love of all persons to love of all bodies, to love of all souls, to Love of Beauty and Truth as such. This is better, but it needn’t be this hierarchical, nor so teleological. And there is no escape from embodiment.

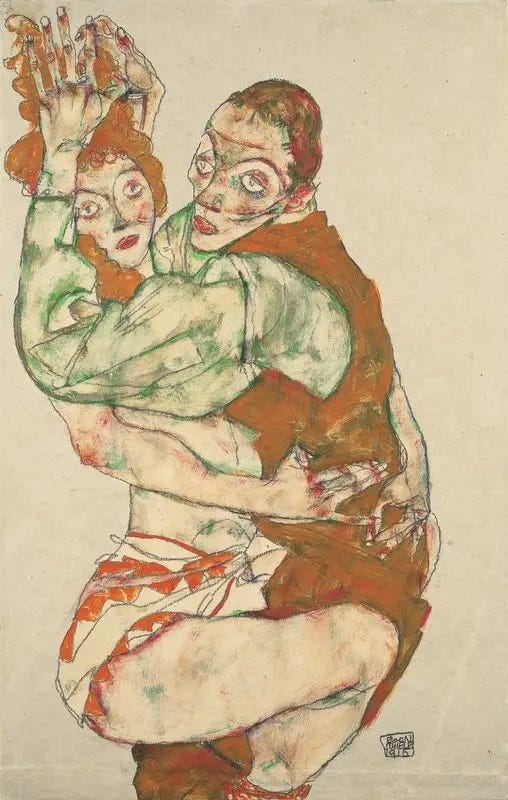

Erotic attachment to particular bodies, which are ensouled, is incarnational gateway and end-in-itself. Eat the flesh, drink the blood: the best fucks are always sacramental. This is how we love the world and everyone in it. And this kind of attachment is shot through with the possibility of loss, and the thing itself.

Love is a complicated subject. Love deserves its own post, its own essay, its own books and bibles. Love makes us do crazy things. Love makes us break the law or at least shatter the canons of whatever counts as conventional wisdom (think Tristan, Isolde, Romeo, Juliet, Heathcliff, Cathy, think John Keats and Fanny Brawne, W.B. Yeats and Maude Gonne, Charles Merriweather and Caril-Anne Fugate, and on and on and on…).

“Whoever loves fulfills” and “transcends the law,” to invoke the born-again Pharisee from Tarsus again. His words find a contemporary echo in pop chanteuse Lana Del Rey—one present day exemplar of a popular romantic tradition that includes Leonard Cohen and Prince, and which fuses holy and profane, undercutting the falsest of false dichotomies—or her lyrics as she marries erotic and religious registers through song:

When all my friends say I should take some space

Love makes us throw everything away to move into a perpetually twilit sylvan world with the beloved one who made you feel alive again among the dark towers downstate. And then you both find more-than-life in that erotic epiphany and communion for what seems an eon until it all crashes and dies.

But, despite an unnamable pain that won’t subside and a wound which doesn’t heal…you don’t regret any of it. You don’t regret any one, any thing. The love you gained (then lost) recolored your gray life in shades of red and pink and blue like some prismatic marriage of bad bruise and aurora borealis. Here is the blood rainbow that will pass before your eyes when you die: something quantifiers, the algorithms they design, and the ersatz, “woke,” moralizers who’ve aligned themselves with the new dispensation can never grasp.

After all this, one day you’re beside an other—in a crowded bar for a first meeting. You recognized her pre-Raphaelite face from some lost streak of former life. Wild and angelic since, as all angelologists know, the only real ones are feral—tearing at a piece of pizza, or you, in an explosion of hunger that doubles as sanctification; this is how they restore the septic earth to health, or how she restored you at least. She sang in a voice all her own: young and old, intelligent and insouciant, resonant with the music of experience beyond her years. Grasping her small form atop a tiny bed in an overheated room: a room which she briefly transformed into refuge against the wreaking world and its contagions through embrace.

You never thought love would come again, but it did, like the Antinomians’ free—and gratuitous—gift of Grace; Grace with hair the color of autumn in her brightest dress of red and orange. You lean into that wisp of a body and listen to her breath rise and fall like those pebbles “the waves draw back, and fling,/ At their return, up the high strand” in the plangent words of the old Victorian school inspector:

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

Cherish it and her while she’s there, knowing it goes. But it is always worth the risk and certainly better than any assortative mating utility maximizing game under whose rules “double texting”—that is, need, longing, and danger—are all prohibited.

Too many present-day interpersonal pathologies emerge from a techno-prosthetic fear of commitment and its risks masked as a fantasy of control rooted in envy of our machines. Günther Anders notably theorized “Promethean shame” or the peculiarly modern desire to emulate our own high tech gadgets.

While our gadgets require service, they don’t have needs after all. Our gadgets are rationally designed to achieve certain ends and our gadgets are virtually immortal, getting better and better with each new model and upgrade. Unlike their human designers: we are centaurs caught between our animal inheritance and the second natures—language, culture, and technology—that we’ve made and that also make us. We are tossed into the world, born bloody and screaming; we are fragile and imperfect creatures dependent on each other as social beings for so much despite any Frankensteinian fantasies of self-making; we grow old, we get sick, we die.

It’s no wonder why the Frankenstein’s among us, the ones who dominate the culture through the digital technosphere, envy their gadgets or at least want to marry them (cf. The Singularity).

For Anders, this shame is one of hypermodernism’s constitutive pathologies and it certainly animates the game. I earlier mentioned rakes and coquettes, and the way these overlapping forms of life have returned in tellingly bloodless and automated forms. Perhaps we might also discover the lineaments of a potential counter-culture—to be arrayed against the game and the larger algorithmic spectacle—in another literary and philosophical movement from the (late) eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: romanticism. Surprise.

In the meantime, ditch the apps and the algorithms and their automated amatory Machiavellianism. Love them even when you lose them:

Unwearied still, lover by lover,

They paddle in the cold

Companionable streams or climb the air;

Their hearts have not grown old;

Passion or conquest, wander where they will,

Attend upon them still.

But now they drift on the still water,

Mysterious, beautiful;

Among what rushes will they build,

By what lake's edge or pool

Delight men's eyes when I awake some day

To find they have flown away?

Thank you for writing this .